Loading...

This project - in reality only ideas - is, as you can see, a bit of fantasy thinking about a National Architecture Prize Competition, which attempts (at least that is what we think) to encourage new ideas about this art. As we are already assuming that it will not be carried out, we have idealised, partly in our thinking and partly in the materialisation of this thought, what a chapel on the traditional pilgrimage route should be today. We have imagined it more like a shrine than a chapel; something that does not in itself interrupt or stop pilgrims, but, on the contrary, helps them to continue along their path - a spiritual path under the stars - that leads to the Apostle.

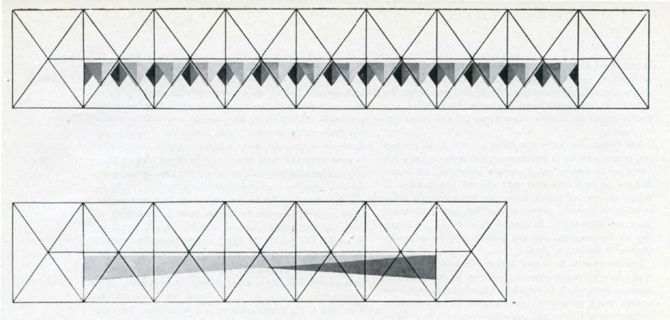

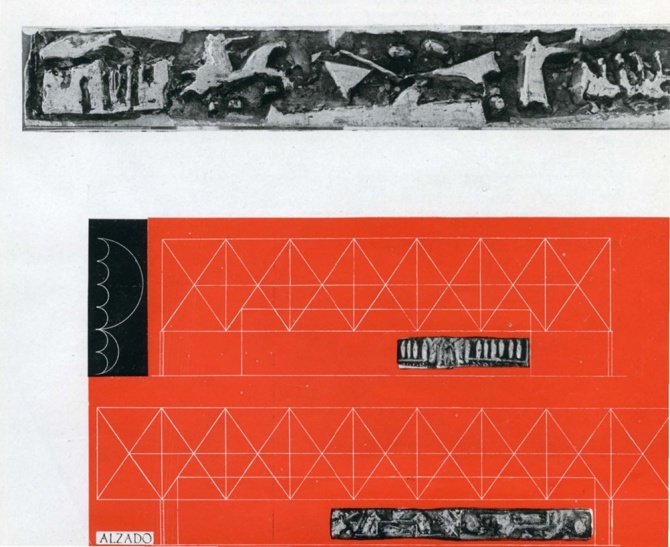

In short, the architecture is based on a spatial geometric structure formed by metallic elements, edges of an ideal polyhedral mesh, which, resting on limited points of a floor plan, situates a multiple network of fixed points in space, which can serve as support - we would rather say suspension or support - for the roof, conceived as a light surface folded in zigzag. Independently of the roof structure, and without touching the latter (as it would not serve either purpose), there is a five-metre-high stone wall which, partly delimiting the interior enclosure, is, in turn, the place for the development of a symbolic theme or legend of the Apostle, according to sketches by the sculptor Jorge de Oteiza.

As a site we have imagined a promontory or hill in the middle of a cornfield. The shining shape of the church will emerge as if on the crest of a wave in the sea of spikes on the Castilian plateau. This brief explanation and the plans you see will give you an idea of what we were thinking; but if you are interested, we will briefly explain some of the points we used as a basis. The problem of the temple is, and has always been, of capital importance for architecture. History shows that the newest, boldest and most daring forms have always been used. If they were churches, religious buildings, it was because the architect, the artist, knew how to infuse them with a high transcendent sense. If we can speak of a religious treatment of an art form, we cannot, however, say that a structure is in itself religious or non-religious. If it is, it is - we repeat - because in its use the artist infused it with that superior stamp.

Based on this hypothesis, it will be understood that we have had no difficulty in resorting to the most audacious, the most advanced forms, the most in keeping with the tools of our industry and our culture: new churches, with new materials, which, artificial today in their first uses, will soon become as natural as those which were available directly to primitive man on the landscape of his days. Are we to renounce them because, being in themselves natural, they have emerged from Nature by means of a tool greater than the primitive flint axe with which primitive man worked the stone, and which today we come to call modern industry? It is in our interest to note the attraction of these first attempts at spatial structure. The fact of its three-dimensional approach seems to us a priori more perfect than any flat resolution, the ideal one only as a particularisation of the general formula to concrete cases.

The innate agoraphobia of the human being has always led to a reduced vision of things, in spaces of lesser dimensions, flat spaces, which then, once familiar, go on to pose limitations on their true spatial reality. First the lintel, the arch, and then, in time, the vault. Even in other arts, such as painting, for example, man seeks, in the first stages of culture, the palana vision, the representation of silhouette, which later, having mastered perspective, becomes three-dimensional, even within the only two dimensions of the painting in which he moves. Spatial metallic forms are not at all common, even less so in the architecture of the church; but once the path has begun in the industrial field, we have not hesitated to apply it to the most elevated architecture. And we hope that the future on this geometry of polyhedrons in space can extract from the new element possibilities of beauty not inferior to those achieved in the architectures of the past with other similar forms of wood or stone. (...)

General information

A chapel on the Camino de Santiago

YEAR

Option to visit

Address

Classification

Construction system

Spatial geometrical structure made of metal elements, five-metre high stone wall

Built area

Awards

Collaborators

Information provided by

Historical Service of the Official College of Architects of Madrid (COAM)

Ministry of Transport, Mobility and Urban Agenda (MITMA)

Website links

https://serviciosdevcarq.gnoss.com/https://serviciosdevcarq.gnoss.com//imagenes/Documentos/imgsem/63/6340/6340fbd6-e35b-4f9e-9f60-d10b90d10d20/b2246ee8-0604-40fd-a947-9b32f40be5b3.jpg, 0000037016/revista-nacional-arquitectura-1955-n161-0002.jpg

https://serviciosdevcarq.gnoss.com//imagenes/Documentos/imgsem/63/6340/6340fbd6-e35b-4f9e-9f60-d10b90d10d20/9fe1bbe1-415e-48da-9d7e-fd0fab33e3ae.jpg, 0000037016/revista-nacional-arquitectura-1955-n161-0003.jpg

https://serviciosdevcarq.gnoss.com//imagenes/Documentos/imgsem/63/6340/6340fbd6-e35b-4f9e-9f60-d10b90d10d20/74198e6c-5b6c-4f41-9366-d5f157fd54d6.jpg, 0000037016/revista-nacional-arquitectura-1955-n161-0004.jpg

https://serviciosdevcarq.gnoss.com//imagenes/Documentos/imgsem/63/6340/6340fbd6-e35b-4f9e-9f60-d10b90d10d20/46fa2506-03e9-4e17-a961-2120a2bbb5cb.jpg, 0000037016/revista-nacional-arquitectura-1955-n161-0007.jpg

https://serviciosdevcarq.gnoss.com//imagenes/Documentos/imgsem/63/6340/6340fbd6-e35b-4f9e-9f60-d10b90d10d20/566be8c7-418d-4a78-868e-82a75966df4d.jpg, 0000037016/revista-nacional-arquitectura-1955-n161-0008.jpg

https://serviciosdevcarq.gnoss.com//imagenes/Documentos/imgsem/63/6340/6340fbd6-e35b-4f9e-9f60-d10b90d10d20/726e8ab7-a5e7-43b8-af65-d87419be9012.jpg, 0000037016/revista-nacional-arquitectura-1955-n161-0009.jpg

https://serviciosdevcarq.gnoss.com//imagenes/Documentos/imgsem/63/6340/6340fbd6-e35b-4f9e-9f60-d10b90d10d20/f88d51fc-7e67-4b7c-a5e1-b5016637a0e1.jpg, 0000037016/revista-nacional-arquitectura-1955-n161-0014.jpg

https://serviciosdevcarq.gnoss.com//imagenes/Documentos/imgsem/63/6340/6340fbd6-e35b-4f9e-9f60-d10b90d10d20/7c80c0e6-4103-4e5e-87d0-3da0a6e6bb8b.jpg, 0000037016/revista-nacional-arquitectura-1955-0006.jpg

https://serviciosdevcarq.gnoss.com//imagenes/Documentos/imgsem/63/6340/6340fbd6-e35b-4f9e-9f60-d10b90d10d20/d8b264a9-0574-4f54-bd6d-881d672469a7.jpg, 0000037016/revista-nacional-arquitectura-1955-n161-0010.jpg